I could have sworn that I wrote a post on Edward Said’s Orientalism last year. Clearly I didn’t – possibly because it might court controversy, because so much has been written already on it, or because frankly I just wasn’t that familiar with Said’s source material. I got the general thrust of the book – that Western academics, poets and politicians have misrepresented the Islamic world and used their image of it as justification for colonialism and foreign policy.

I could have sworn that I wrote a post on Edward Said’s Orientalism last year. Clearly I didn’t – possibly because it might court controversy, because so much has been written already on it, or because frankly I just wasn’t that familiar with Said’s source material. I got the general thrust of the book – that Western academics, poets and politicians have misrepresented the Islamic world and used their image of it as justification for colonialism and foreign policy.

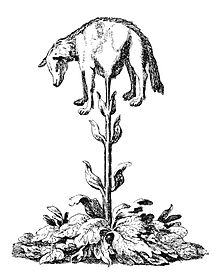

Robert Irwin is very familiar with the source material; at least for the Orientalist scholars of the title. He begins starts this rebuttal of Said’s book by condemning his misrepresentation of these scholars. He begins by slowly going through the history of the representation of Islam in the “West”. In the medieval era I recognise some stories from Wonders Will Never Cease like the Vegetable Lamb or Tartary, or Ramon Llull being tempted by a woman who turns out to be disfigured by cancer and praises his piety. Fundamentally, those medieval scholars are unfamiliar with the land, culture or religion; and as he will later point out, rather than truly seeing Muslims as “other”, they compare them to what they know: Arian heretics or Christian sects.

As contact was made, works were translated and writers started to travel we get the likes of Guillaume Postel – looked over by the Inquisition as more insane than heretical; with a Vatican official declaring that “though his ideas were definitely heretical ‘no one, fortunately, could possibly understand them except the author'”. Orientalist scholars are seen as a small fringe to the mainstream, generally seen as eccentric at best. Later, the likes of De Sacy or Hammer-Purgstall do still see Islam through the prism of their own experiences, for example seeing the Druzes as atheist revolutionaries in the Carbonari mold. But the way Irwin presents this is relatively benign, it’s a search for a familiar reference and to understand unfamiliar cultures. Although this had a big impact on the field of Orientalism, Irwin sees little on wider European culture. For the most part, those who pushed for colonialism were dismissive of the scholars, and those who administered it had Greek and Roman culture as their reference rather than the work of the Orientalists.

As contact was made, works were translated and writers started to travel we get the likes of Guillaume Postel – looked over by the Inquisition as more insane than heretical; with a Vatican official declaring that “though his ideas were definitely heretical ‘no one, fortunately, could possibly understand them except the author'”. Orientalist scholars are seen as a small fringe to the mainstream, generally seen as eccentric at best. Later, the likes of De Sacy or Hammer-Purgstall do still see Islam through the prism of their own experiences, for example seeing the Druzes as atheist revolutionaries in the Carbonari mold. But the way Irwin presents this is relatively benign, it’s a search for a familiar reference and to understand unfamiliar cultures. Although this had a big impact on the field of Orientalism, Irwin sees little on wider European culture. For the most part, those who pushed for colonialism were dismissive of the scholars, and those who administered it had Greek and Roman culture as their reference rather than the work of the Orientalists.

That’s not to say that it was all sunshine and enlightenment: there are plenty of stories like “Professor Hamilton Gibb warned [James, 50s Durham lecturer] Craig against spending time in the middle east as ‘it will corrupt your classical'”. In Irwin’s view, the best work in the field, the work that sets its direction, was being produced by German scholars in the 19th century, or by Hungarian Jews like Goldhizer. The British universities were moribund, and the French were mostly just following the trend. Their views of history were also heavily informed by the cyclic rise and fall of Ibn Khaldun’s work. Both of these are an issue for Said, who (even in corrections) saw the Germans and eastern Europeans are irrelevant.

In his chapter on the Post-war Hey Day Irwin describes carefully how Arab studies in Arab countries have lagged behind (Albert Hourani suggested that the good scholars just get jobs in the west), and so the English speaking writers continued to attempt to fill the gap. That’s not to say all Islamic scholarship has been slow – Turkey is very successful – though continuously ignored by both Said and Irwin. He picks out politically disagreeable authors like Bernard Lewis and picks out their early work of merit: “anyone who wishes to determine Lewis’s merits as an Orientalist has to engage with (emergence of modern turkey) and other works of the sixties.”. Or the many French orientalists who stood against French North African colonisation. For him, Said has dismissed worthy scholars on political grounds, and ignored politically inconvenient sources.

As we get to the modern day, he tackles Said’s criticism of specialist scholars making generalist comments on parts of the Middle East outside their geographical or temporal expertise. He justifies this by the small number of academic positions, and sheer lack of interest in the subject. When undergraduate courses in Arabic are being closed down, and even senior positions go unfilled; it is easier for an academic to write a general piece, or claim political relevance, than it is to beg for funding for specialist topics (“Coins of the Almohads” vs “A history of the Arab Peoples”?).

Finally we reach his personal condemnation of Said. It’s a polemic, a good polemic; he points out many of Said’s errors and Said’s poor attitude to criticism. There is a bit of a personal attack at Said’s upbringing – wealthier and less Palestinian than later suggested – that seems unnecessary. However, it is a pretty convincing demolition of Said’s use and understanding of the academic sources. There’s a brief section on other “enemies”, but for the most part these are less convincing that Said and easier to dismiss (either you think the Quran is received wisdom from God, or it is not; arguments that Jews should not be studying Islam …). Ziauddin Sardar is more interesting, but Irwin again narrows in on the detail. Finally, he is actually quite complementary of Muhsin Mahdi – which is nice.

In the end though, it could be said that both Irwin and Said miss the point. Irwin shows that the Orientalists themselves were often misrepresented – but he steers clear of the wider view that British and French cultural attitudes to Islam allowed their later (and current) behaviour in the Middle East and North Africa. His book aims narrowly at clearing the academic scholars, then extrapolates this into a dismissal of Said and his followers. Where an Orientalist is undeniably involved in Imperialist projects, Irwin sees it as an outlier; Irwin’s is a very individualist approach to the topic – everyone doing their own thing for their own reasons, wider cultural trends playing a minor role. Said may have been ambiguous in his detail – but there’s a fundamental point about the difficulty of removing politics and cultural bias from pure academia that still stands despite Irwin’s rebuttal.

In medieval tales, the Vegetable Lamb or Scythian Lamb or Barometz is a plant-animal hybrid that lives in central Asia, or Russia, or perhaps the Black Sea area near Persia. It consists of a lamb that is rooted to the earth by a umbilical cord like stem. The lamb can flex this stem such that is can eat grass in the immediate circle around it, but is prevented from moving beyond that and must then either starve or drop off the plant as a ripened sheep (sources seem divided as to which one; or perhaps just generally confused).

In medieval tales, the Vegetable Lamb or Scythian Lamb or Barometz is a plant-animal hybrid that lives in central Asia, or Russia, or perhaps the Black Sea area near Persia. It consists of a lamb that is rooted to the earth by a umbilical cord like stem. The lamb can flex this stem such that is can eat grass in the immediate circle around it, but is prevented from moving beyond that and must then either starve or drop off the plant as a ripened sheep (sources seem divided as to which one; or perhaps just generally confused).

The quote from The Guardian on the back of the book compared it to a mix of AS Byatt and Terry Pratchett. Perhaps, but I’d throw in Hilary Mantel and Umberto Eco. There’s something in the mix of the realist portrayal of medieval life blending with constant surrealist tangents. What they really meant though was that the book will reward multiple readings, it is enjoyable first time round but there are so many allusions and references that you can come back again and again.

The quote from The Guardian on the back of the book compared it to a mix of AS Byatt and Terry Pratchett. Perhaps, but I’d throw in Hilary Mantel and Umberto Eco. There’s something in the mix of the realist portrayal of medieval life blending with constant surrealist tangents. What they really meant though was that the book will reward multiple readings, it is enjoyable first time round but there are so many allusions and references that you can come back again and again.